Pin Up Casino Azərbaycan Rəsmi Saytına 2026

Pin Up Casino rəsmi saytı – Azərbaycanda etibarlı və tanınmış onlayn mərc platformalarından biridir. Burada istifadəçilər sürətli qeydiyyat sayəsində cəmi bir neçə dəqiqəyə Pin Up kazino oyunlarını oynamağa başlaya bilirlər. Sayt beynəlxalq lisenziyaya malikdir, bu da əməliyyatların qanuni və təhlükəsiz aparılmasına zəmanət verir. Pin Up Casino-da siz idman mərcləri bölməsi ilə yanaşı, 6000-dən çox şans oyunundan seçim edə bilərsiniz: canlı dilerlərlə live kazino, slotlar, crash oyunlar, cekpotlu oyunlar və stolüstü növlər. Rahat naviqasiya həm veb-saytda, həm də Pinup Casino tətbiqində mövcuddur.Oyunların keyfiyyəti mobil cihazlarda masaüstü versiya ilə eynidir. Slotlar, canlı diler oyunları və crash oyunlar yüksək sürətlə açılır və internet sürəti zəif olduqda belə dayanmadan işləyir.

Bəzən əsas domenlərə texniki səbəblər və ya provayder bloklamaları görə giriş məhdudlaşa bilər. Bu halda, Pin-Up AZ istifadəçilərinə cari giriş linkləri və işləyən alternativ ünvanlar təqdim olunur: pin-up 141 casino, pin-up 360, pin-up 085 və pin-up 306 casino.

| Təsis ili 📆 | 2016 |

| Lisenziya 🔰 | Curacao 8048/JAZ2017-003 |

| Mobil tətbiq 📱 | IOS və Android üçün yüklənə bilər |

| Dəstəklənən dillər 🌐 | Azərbaycan, Rus, Türk, Portuqal, Ingilis, Qazax və Ukrayna |

| Qeydiyyat bonusu 🎯 | İlk depozitdə 10,000 AZN + 250 pulsuz fırlanma məbləğində 100% bonus |

| Bonuslar və aksiyalar 🎁 | "Həftənin slotu" üçün pulsuz fırlanmalar, 100% mərc sığortası, həftəlik 10% cashback (10000 AZN-ə qədər), hədiyyə qutuları, VIP proqram, promokodlar, İkiqat Bazar ertəsi, jackpotlar |

| Valyutalar 💸 | AZN, EUR, USD, KZT, ARS, IDR, UZS, INR, PEN, CLP, CAD, MXN, TRY, BDT, BRL |

| Ödəniş sistemləri 💰 | Visa, Mastercard, E-cüzdanlar (E-Manat, Piastrix, Perfect Money), Kriptovalyutalar (BinancePay, Bitcoin, Ethereum və s.) |

| Minimum mərc 🎲 | 1 AZN |

| Minimum depozit ⏬ | 9 AZN |

| Minimum çıxarış ⏬ | 10 AZN |

| Maksimum bir dəfəlik ödəniş ⏫ | 200,000 AZN |

| Provayderlər 🔁 | Novomatic, PG Soft, Amatic, Evolution, Belatra, Netent, Play’n’Go, Pragmatic Play, Playson |

| Oyunlar 🖥 | 7000-dən çox oyun: slotlar, canlı diler oyunları, poker, blackjack, bakara, keno, skreç kartları, idman mərcləri |

| Əsas idman mərcləri ⚽️ | 50-dən çox idman növü, o cümlədən canlı mərclər |

| Dəstək 📞 | @PinUpSupportBot — Telegram; 24/7 onlayn dəstək sayt üzərindən mövcuddur |

| Elektron poçt 💻 | [email protected] |

Candy Boom

Aviator

Space XY

Jet X

Gold Digger Megaways

Penalty Shoot-Out

Spaceman

Pin Up-un üstünlükləri və çatışmazlıqları

Pin up AZ, digər bukmeker kontorlarından fərqli olaraq vacib üstünlükləri ilə Azərbaycanda böyük populyarlıq qazanıb.

Sadə qeydiyyat və istifadəçi məlumatlarının qorunmasına zəmanət;

Saytın cari ünvanına sürətli giriş;

Android (APK) və iOS üçün pin-up casino indir tətbiqini yükləmək imkanı;

10 AZN-dən komissiyasız sürətli vəsait çıxarışı;

Lisenziyalı provayderlərdən 5000-dən çox oyun;

Slotlarda demo rejimində pulsuz oynamaq imkanı;

İdman mərclərində yüksək əmsallar və nəticələrin sürətli hesablanması.

Azərbaycan dilində 24/7 çalışan operativ dəstək xidməti;

Asanlıqla əldə edilə bilən və aktivləşdirilən bonuslar, o cümlədən depozitsiz bonuslar.

Sayta giriş çətin ola bilər, bu halda pin up 7/24 giriş üçün aktual ünvanı tapmaq lazımdır;

Maksimum vəsait çıxarış limiti – bir müraciət üçün 19,000 AZN

Bonusların mərc tələbləri bir qədər mürəkkəbdir.

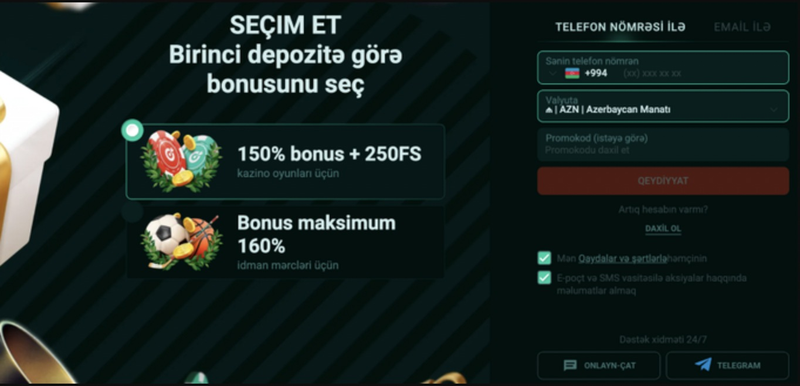

Pin up Kazino saytında qeydiyyat

Rəsmi Pin up casino saytında sürətli və sadə qeydiyyatdan keçdikdən dərhal sonra real pulla oyun oynamağa başlaya bilərsiniz. Qeydiyyat üsulunu özünüz seçirsiniz, amma biz telefon nömrəsi ilə giriş üsulunu tövsiyə edirik. Hesab yaratmaq üçün saytı açın və “Qeydiyyat” düyməsinə klikləyin. Qeydiyyatdan keçdikdən sonra xoş gəlmisiniz bonusunu aktivləşdirə biləcəksiniz. Açılan formada aşağıdakı məlumatları daxil etməlisiniz:

- Telefon nömrəsi və ya e-mail ünvanı;

- Giriş parolu;

- Valyuta seçimi;

- Qaydalarla razı olduğunuzu təsdiqləyin;

- Promokod aktivləşdirin (əgər varsa) və qarşılama bonusunu seçin.

Qeydiyyat prosesi cəmi 1 dəqiqə çəkir və hesabınız dərhal aktiv olur. Amma ilk olaraq profil məlumatlarını – oyunçunun adı, ünvanı və digər vacib məlumatları tam şəkildə doldurmalısınız. Bu məlumatlar verifikasiya zamanı yoxlanılır. Sənədlərinizi şəxsi kabinetinizdən yükləyin və 2-3 gün ərzində yoxlama tamamlanacaq.

Bütün yeni oyunçular verifikasiya prosesindən keçməlidirlər, yalnız bundan sonra uduşları çıxarmaq mümkün olacaq. Şəxsiyyəti təsdiqləyən sənədlər barədə narahat olmağa dəyməz, onlar yalnız Pin Up Azerbaycan onlayn kazinosunun daxili yoxlanışı üçün tələb olunur. Sizin bütün şəxsi məlumatlarınız 100% məxfi saxlanılır və üçüncü tərəflərlə paylaşılmır.

Pin Up AZ Kazinoya giriş üçün həmişə işlək olan ünvanları izləyin. Bu linklər rəsmi sayt kimi görünür, amma bir az fərqlənir. Məsələn: pin-up 141 casino, pin up 360, pin up 085. Bunlar təhlükəsiz və işlək ünvanlardır, ona görə də 7/24 problemsiz daxil ola bilərsiniz – heç bir VPN və əlavə servisə ehtiyac yoxdur.

Pin-Up Casino AZ ödəniş üsullarına görə limitlər

Pin-Up Casino AZ saytında hər bir ödəniş üsulu üçün ayrıca minimum və maksimum yatırma və çıxarış limitləri təyin olunub.

| Ödəniş üsulu | Min. depozit | Maks. depozit | Min. çıxarış | Maks. çıxarış |

| Card to Card | 10 ₼ | 3 000 ₼ | 30 ₼ | 1 500 ₼ |

| Visa / MasterCard | 9 ₼ | 5 000 ₼ | 10 ₼ | 6 700 ₼ |

| Mpay | 50 ₼ | 1 000 ₼ | 10 ₼ | 6 700 ₼ |

| M10 pulqabı | 15 ₼ | 2 000 ₼ | 10 ₼ | 6 700 ₼ |

| Telegram bot (köçürmə) | 20 ₼ | 2 500 ₼ | 20 ₼ | 6 700 ₼ |

| Kriptovalyuta (USDT TRC-20, BTC və s.) | 10 USDT | məhdudiyyətsiz | 25 ₼ | 1 650 000 ₼ |

Pin-Up Casino AZ saytında depozit etdiyiniz anda hansı bonusu alacağınızı dərhal görmək çox rahatdır.

Pin Up Bet Casino-da idman mərcləri

Pin Up Bet Casino saytında idman mərcləri, onlayn kazino bölməsi qədər populyardır. Hesab birdir – ayrıca daxil olmağa ehtiyac yoxdur, həm kazino, həm də idman mərcləri üçün eyni balansdan istifadə edilir.

Rəsmi Pin Up Bet saytının əsas səhifəsində siz dərhal ən aktual matçları və yüksək əmsalları görəcəksiniz. Canlı mərclər (Live) bölməsində oyun zamanı əmsallar daim dəyişir. Ən sərfəli məqamda mərc etmək vacibdir. Xüsusilə futbol oyunları üçün canlı yayım funksiyası da mövcuddur.

Tövsiyəmiz: yalnız qaydalarını bildiyiniz oyunlara və komandaların hazırkı formasını araşdırdıqdan sonra mərc edin. Təsadüfi seçimlərə arxalanmayın – statistikanı izləyin.

Ümumilikdə 35-dən çox idman növü üzrə mərc etmək mümkündür, o cümlədən:

- Futbol – Azərbaycan Premyer Liqası, İngiltərə Premyer Liqası, İspaniya La Liqası, İtaliya A Seriyası, UEFA Çempionlar Liqası və s.

- Hokkey – NHL, KHL, İsveç SHL, Finlandiya Liigası

- Tennis – ATP, WTA turnirləri və Grand Slam yarışları

- Basketbol – NBA, Euroleague, Türkiyə Super Liqası

- Həndbol, boks, güləş, at yarışı və digər idman növləri.

Əgər siz virtual idman və ya e-idman həvəskarısınızsa – burada Dota 2, League of Legends, CS:GO, Valorant və digər kiberidman intizamlarına canlı baxmaq və mərc etmək imkanı da var.

Minimum mərc məbləği – cəmi 1 manatdır. Matçın nəticələri təsdiqləndikdən dərhal sonra mərcin.

Mobil tətbiq: Pin Up Casino yüklə

Pin Up Casino AZ mobil tətbiqini yükləyin və kazino oyunlarını birbaşa telefonunuzda oynayın. Bu, saytda və ya mobil brauzerdə oynamadan daha rahatdır. Tətbiq həm Android, həm də iOS cihazları üçün əlçatandır, lakin yalnız rəsmi saytdan yükləmək mümkündür. Android üçün tətbiqi yükləmək üçün mobil brauzerdə saytı açın və “Mobil tətbiqlər” bölməsinə daxil olun:

- “Pin Up yüklə” düyməsinə basın;

- Telefonunuzun parametrlərində naməlum mənbələrdən quraşdırmaya icazə verin;

- APK faylını yükləyin və açın;

- Quraşdırma avtomatik başlayacaq və tətbiq 1 dəqiqə ərzində telefonunuzda hazır olacaq.

Tətbiqdən istifadə 24/7 mümkündür – sadəcə hesabınıza daxil olun və dərhal oynamağa başlayın. Mobil versiya da bütün funksiyaları dəstəkləyir, lakin tətbiq daha rahat interfeys təqdim edir. Bütün oyunlar problemsiz açılır. Xüsusilə Pin Up Aviator oyunu sensor idarəetmə üçün mükəmməldir və real qazanclar təklif edir.

Tətbiqi təxminən ayda 1 dəfə yeniləmək lazımdır ki, bütün yeni funksiyalar işləsin. Proqramı yükləməyə görə ayrıca bonus yoxdur, amma bütün aksiyalar burada da keçərlidir. Yenidən qeydiyyat etməyə ehtiyac yoxdur – tətbiqdə Pin Up Casino giriş bloklanmır, bu səbəbdən daim işlək ünvana ehtiyac qalmır.

Pin Up Casino mobil tətbiqi oyunçulara həm kazino, həm də idman mərclərinə vahid interfeysdən çıxış imkanı verir. İstifadəçi şəxsi kabinetinə daxil olduqdan sonra balansını idarə edə, depozit edə və vəsait çıxara bilir. Tətbiqdə bütün ödəniş üsulları – bank kartları, elektron cüzdanlar və kriptovalyutalar – tam işləkdir. Əməliyyatların statusunu real vaxtda izləmək mümkündür.

Tətbiq eyni zamanda push-bildirişlər göndərir. Bu o deməkdir ki, siz yeni aksiyalar, bonus kodları, canlı matçlar və turnirlər barədə ilk xəbər alanlardan olursunuz. Beləliklə, vacib fürsətləri qaçırmadan dərhal reaksiya verə bilərsiniz.

Android tətbiqi artık mevcut

Tez-tez verilən suallar

Pin-up nədir?

Pin-up – Carletta N.V. şirkətinə məxsus beynəlxalq mərc şirkəti və kazinodur. Brend lisenziyalıdır və buna görə də 2016-cı ildən etibarən Azərbaycanda qanuni şəkildə fəaliyyət göstərir.

Pin-up etibarlıdırmı?

Şübhəsiz ki, lisenziya və tərəfdaşlar hesabına Pin-up kazinosu məlumatların təhlükəsizliyini, ödənişləri və oyunun dürüstlüyünü təmin edir. “Məxfilik siyasəti” və “İstifadə şərtləri”ndə qeyd olunanların hamısına ciddi şəkildə əməl olunur.

Pin-up hesabımdan pulu necə tez çıxara bilərəm?

Profilinizdə “Kassa” bölməsi var, ora daxil olun və pul çıxarma üsulunu seçin. Məbləği və ödəniş rekvizitlərini (məsələn, elektron pulqabı və ya bank hesabı nömrəsi) göstərin. Ödənişi hesabınızdakı status vasitəsilə izləyə bilərsiniz.

Tətbiqi necə yükləmək və telefonda kazinoda oynamaq olar?

Pin-up mobil tətbiqi yalnız Android üçün APK formatında mövcuddur. APK faylını rəsmi saytdan, mobil brauzerdən aktual ünvana daxil olaraq yükləmək lazımdır.

Pin-up hansı ödəniş və pul çıxarma üsullarını təklif edir?

Balansı artırmaq üçün Visa/Mastercard kartları, mpay onlayn köçürmə sistemi, m10 mobil pulqabı, köçürmə və kriptovalyuta istifadə edə bilərsiniz. Pul çıxarma üçün də eyni üsullar keçərlidir, lakin limitlər bir qədər fərqlənir.

Pul çıxarma üçün limit varmı?

Bəli, gündəlik maksimum məbləğ 10000 AZN-dir. Aylıq sabit limit yoxdur. VIP oyunçular üçün bu məhdudiyyətlər fərdidir.

Kataloqda real pul ilə oynamaq üçün ən yaxşı oyun hansıdır?

Spribe şirkətindən Pin-up Aviator oyununu oynayın – bu, Crash janrında sadə bir oyundur və x10.000-ə qədər uduş imkanı verir (bir raund üçün 2000 AZN-ə qədər).